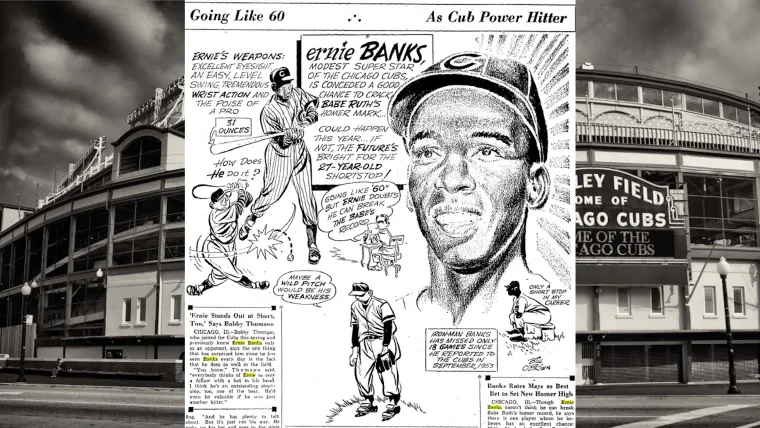

This story, by Baseball Hall of Famer Jerome Holtzman, first appeared in the Sept. 3, 1958, issue of The Sporting News under the headline “Banks Given Best Chance to Tie Bambino” as Chicago icon Ernie Banks was on his way to the first of consecutive NL MVP awards. Only five years earlier Banks’ name had first appeared in TSN in connection with the Cubs (a “Negro shortstop from the Kansas City Monarchs”) as one of four Black players, the first in franchise history, to arrive in Chicago. The future Mr. Cub’s first of 512 major-league homers was chronicled two weeks later (he also had a triple, a single and three RBIs that day in St. Louis).

CHICAGO — It was a Sunday morning at Wrigley Field and the Cubs were preparing for a double-header. They were taking batting practice and Ernie Banks was in the cage. He took four swings and four balls sailed into the bleachers. Two dipped into the left field stand and the other two high, towering shots dropped well beyond the 400-foot mark in dead center.

As the kids in the bleacher's scrambled for these latest Ernie Banks souvenirs, a mild argument developed behind the batting cage. "It's his eyes,” said Jim Bolger, the Cubs’ utility outfielder and pinch-hitter. "No," said Walt (Moose) Moryn, "it's his timing and coordination." Dale Long disagreed. "It's the wrists," he said.

The grizzled old Rogers Hornsby, greatest righthanded hitter in baseball history and now a batting coach with the Cubs, listened in silence. Finally, the Rajah spoke, an air of finality in his voice. "It's all those things put together," he said, "Good eyes, timing, the wrists and the follow through."

He Puzzles Fans

That ended the discussion and should answer, also, the one question that baseball fans are constantly asking about Ernie Banks. When they see Ernie Banks in the flesh, a lean, wiry 178-pounder, their reaction is inevitably the same: "How does he do it? Where does he get the power?”

TSN ARCHIVES: Walter Payton’s lessons in greatness (Nov. 15, 1999)

The power, of course, is there, for Banks already has established himself as the best slugging shortstop in baseball history. He did this with 41 homers in 1955, and now, three years later, he is challenging the game's homer giants: Babe Ruth, Jimmie Foxx, Hank Greenberg and Hack Wilson.

By the fourth week in August, Banks had clubbed 42 home runs, just three games behind the Bambino's record 60-homer pace. But whereas Ruth's other challengers wilted in September, Banks has given evidence that he too, can hit in the stretch. He slugged 13 homers last September. Perhaps he will do as well or better this year.

Many baseball men contend that Banks has the best chance of anyone playing today of equalling or surpassing Ruth's 60, the most sacred single record in the game. Cub Manager Bob Scheffing is among them and offers this one, simple reason:

“Ernie is getting better all the time," Schelling says. "He still has his best years ahead of him."

At 27, Banks is a five-year big league veteran and a baseball fixture. Prior to '58, he had clubbed 136 major league homers and had a three-year homer average (1955-56-57) of 38.3. It is this consistency, plus the fact that he is not a streak hitter, that makes him the No. 1 threat to Ruth's record today.

Banks himself, though, says Ruth's record is beyond his reach. Asked if he thought he could break the record, he replied, his generally phlegmatic expression actually startled by the question: "Who, me? You can put all my homers end to end and I'd never match Ruth."

TSN ARCHIVES: Michael Jordan retired; Bob Costas weighed in (Jan. 25, 1999)

Banks, however, suffers from extreme modesty. There is probably no other major league star who minimizes and soft-pedals his achievements as Banks does. He almost never speaks about himself, especially when with a group. Ask him about hitting and he'll talk in surprisingly vivid detail of Stan Musial, Willie Mays or Frank Thomas. He almost ever mentions Ernie Banks.

"I've never heard Ernier make a boastful remark," says Manager Scheffing. "And he has plenty to talk about. But it's just not his way. He picks up his bat and goes to the plate and whether he hits a home run or strikes out, he comes back without saying a word."

This Sphinx-like exterior once prompted Stan Hack (Banks' second manager; Phi] Cavarretta was his first) to make the statement which has since been widely quoted: "After he hits a homer, he comes back to the bench looking as if he did something wrong."

But this is just Banks' outward manner and actually quite superficial. He says that he gets quite excited. His stomach jumps, his heart pumps fast and he is extremely tense, particularly before a new series, and when he comes to bat for the first time in every game.

"I fight it all the time," he explained. "Whenever I'm tense, I'm not at my best. I try to relax."

Banks then elaborated and told of several instances during the 1955 season, the year that he set the homer record for shortstops and also set the major league mark of five grand slams in one season.

TSN ARCHIVES: The moment Michael Jordan became the NBA’s best player (June 24, 1991)

“When I hit the fourth grand-slammer, I didn't know I had tied the record. But after that I had about three or four chances for that fifth grand-slammer and failed. Every time I went to the plate. I was saying to myself, 'This is my chance to get No. 5.

"I was too tense. Finally, one day in St. Louis, I came up with the bases loaded. Lindy McDaniel was pitching. I had forgotten all about the record. I was thinking of only driving some runs in. That's when i hit my fifth grand-slammer."

Relaxation, then, is a prime factor in Banks’ success. He can't eat, for example, until almost two hours after a game. When he is at home, he listens to music, primarily for relaxation. The pleasure of Count Basie, Lionel Hampton and Nat King Cole is secondary.

Banks is careful also about his diet. He is much indebted, he says, to Stan Musial, who long ago advised him to eat a lot of vegetables and salads, especially in the hot weather. Banks drinks at least a quart of fruit juices daily and seldom eats fried foods.

Musial is one of Banks' two baseball idols. The other is Jackie Robinson, the former Dodger star. Banks admires Musial as a great player and for his conduct, on and off the field. He regards Robinson as an ideal athlete and competitor and as the most versatile player of his time.

Like Robinson, Banks jumped to the majors from the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League. But unlike Robinson, he never thought he would some day be a star. He always considered himself just another ball player with ordinary talent.

As a boy, he never dreamed of some day making the big leagues and didn't play his first game of baseball until he was 17. He was a three-sport man at Booker T. Washington High School in Dallas, lettering in basketball, football and track. He was offered several football scholarships but turned them down.

His high school didn't have a baseball team, but he played softball constantly, mostly in church and YMCA leagues. One day, Bill Blair, a friend of the family, asked him if he wanted to play with the Amarillo Colts, a Negro semi-pro team that played in Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas and Nebraska.

One of 12 children, Banks asked his parents for permission to leave home. His father, Eddie, a former semi-pro catcher, was delighted with the fact that his son would have a chance to play baseball. Ernie's mother also agreed, so off he went with Bill Blair to Amarillo.

TSN ARCHIVES: Bobby Hull, the Golden Jet of hockey (March 19, 1966)

He played with Amarillo for two seasons, then attracted the attention of the Kansas City Monarchs. He joined the Monarchs in 1950 and was immediately installed as the team's regular shortstop. He had a good year, hitting 22 homers — the first inkling of his power.

He then spent the next two years in the Army and rejoined the Monarchs in April of 1953. He twisted his ankle sliding into a base in July and went home to Dallas to recuperate. He was home for nine days and during this time was offered a chance to work out with the Dallas Eagles of the Texas League.

"It was odd the way it happened." Banks recalled. "I was sitting on the doorstep one day when Buzz Clarkson came up to me and asked if I wanted to work out. Clarkson had been in the big leagues briefly and was then playing with Dallas.

"I was glad for the chance and so the next night took batting practice with Dallas. I remember it very well because I took four or five swings and I must have hit two or three balls out of the park. Then I took infield practice.

"At the time, Jerry Doggett (now a Los Angeles radio announcer) was working the Dallas games. Jerry came up.to me and said, 'We could use you here.' He intimated that the Dallas owners were interested in buying me from the Monarchs. That was the first time I realized I had a chance to get into Organized Ball.

"But nothing much happened and I rejoined the Monarchs. I didn't particularly like the life. I was lonesome and one day I went up to Tom Baird (the Monarchs' owner) and mentioned that I was thinking about quitting.

"Mr. Baird sat me down and said, "Now, listen. I don't think you know this, but you're going to wind up in the big leagues. The Chicago White Sox are interested in you.

"That news almost floored me,” Banks continued. "I sat tight and as it turned out the Cubs and not the Sox were the ones who were interested. My contract was sold to the Cubs for $15,000. What did I get? Ten dollars and a plane ticket from Pittsburgh to Chicago."

Banks played his last game for the Monarchs against the Indianapolis Clowns at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. The date was September 14, 1953. The next day, a Saturday, he arrived in Chicago and was given uniform No. 14. It is significant that the first time he stepped into the batting cage, he hit the ball out of the park.

Phil Cavarretta then managed the Cubs and Banks sat on the bench for the next three days. His arrival also coincided with that of Gene Baker, the star shortstop from Los Angeles of the Pacific Coast League. They were the first Negroes ever to play for the Cubs.

Banks got into a game the fourth day he was with the team. "You're playing shortstop today,” Cavarrelta told him, and Banks was in the starting lineup to stay. He proceeded to play in 474 games — a consecutive-game record from the start of a major league career.

His first big league homer wasn't long in coming. It came off Gerry Staley, then one of the stars of the Cardinals' staff. He also hit his only other homer of the '53 season off Staley.

The next season, in 1954, Banks hit 19 homers. The following year he clubbed 44, then slumped to 28 before he connected for 43 last year, just missing tying the Braves' Hank Aaron for the National League homer crown. Aaron finished with 44.

Banks, himself, admits that he is a better hitter today than he was last year. Manager Scheffing say's so, too, and points out that Ernie knows the strike zone better and is also hitting to the opposite field more often.

"He has no holes," Scheffing said. "He has the perfect swing and now that he doesn't go for bad balls, he's the toughest man in the league to pitch to. I won't say he's going to break Ruth's record. But I will say this: He's got a better chance of breaking it than anyone in the game today."